Sandra Day O’Connor, appointed by Ronald Reagan to be the first woman on the Supreme Court, has published a profound op-ed in The New York Times this morning, calling for a massive effort to cure Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). In so writing, O’Connor and her two co-authors echo Maria Shriver, who has been making the same argument about AD: It’s cheaper, as well as more compassionate, to cure the malady than it is to care for it. As the op-ed notes, we don’t spend money on polio anymore, not because we streamlined treatment, or because we are heartless, but because we eliminated the disease itself. Quality is free, they say, and freedom from disease is almost free.

Yet for the last two years--indeed, for the past two decades--Americans have been told that the key issue in health and medicine is national health insurance. The Democrats won the policy battle in Washington, although it appears to be a Pyrrhic victory--Democrats seem destined to be drubbed at the polls this November. The voters don’t seem to agree with Vice President Biden that Obamacare is a big bleeping deal--or if they do, they don’t particularly like the deal.

For their part, Republicans seem focused on repealing Obamacare, as part of an overall effort to reduce the size of government. But even if Obamacare were repealed “lock, stock, and barrel,” as Rep. Mike Pence (R-IN) has pledged to do, joined by many other GOPers, the right should understand the limits to such a repeal. Deracinating Obamacare would not make it more likely that treatments for AD will emerge from laboratories. The roadblock to better medicine is not that someone is getting health insurance (although more aggressive efforts to restrict costs could take a toll on research funding). Instead, the current roadblocks have more to do with regulations, a capital shortage in the R&D sector, and the pervasive influence of the tort bar. It would be a shame if Republicans invested the next two years in repealing Obamacare, only to find--even if they are successful in their repeal-quest--that the mounting medical cost of AD has dwarfed whatever budget savings they might achieve in healthcare.

The two issues, health insurance and medical research, are essentially different. They are, to use the voguish business term, different “silos.” Unfortunately for the health of all of us, the health-insurance silo has come to predominate, at least in Washington, over the medical-research silo.

But to put it bluntly, medical research is more important than health insurance. If our population were still stalked by ancient killers, such as the plague, or smallpox, or tuberculosis, it wouldn’t matter much if we had insurance. Indeed, if we are stalked in the future by new threats, such as AD and diabetes, insurance will matter little--and might well be unaffordable. The key issue of life and death is the delivery of health, not health insurance.

And so, in the political distance, we can see a great wheel turning on healthcare policy, as we shift from reactive to preemptive thinking about medicine and health. In reactive thinking, we pay for the disease after it happens. That’s good and compassionate, but it’s a shame that the spending comes after the affliction has struck. And that is, in fact, where most of our healthcare money goes--to help people after they get sick. Indeed, only about 4 cents out of every healthcare dollar in the US goes to medical R&D; the other 96 percent goes to treatment. We can liken those expenditures to the capital budget and the operating budget in a business. But it is that capital expenditure that offers the only hope for truly “bending the curve” on AD. We will defeat AD by preempting it. If we merely treat AD reactively, then it has defeated us.

After considering the psychic and financial cost of AD, O’Connor, Dr. Stanley Prusiner, recipient of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Medicine, now director of the Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases at the University of California, San Francisco, as well as Ken Dychtwald, a psychologist and gerontologist, lay out their plan:

Just as President John F. Kennedy, in 1961, dedicated the United States to landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade, we must now set a goal of stopping Alzheimer’s by 2020. We must deploy sufficient resources, scientific talent and problem-solving technologies to save our collective future.

As things stand today, for each penny the National Institutes of Health spends on Alzheimer’s research, we spend more than $3.50 on caring for people with the condition. This explains why the financial cost of not conducting adequate research is so high. The United States spends $172 billion a year to care for people with Alzheimer’s. By 2020 the cumulative price tag, in current dollars, will be $2 trillion, and by 2050, $20 trillion.

If we could simply postpone the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by five years, a large share of nursing home beds in the United States would empty. And if we could eliminate it, as Jonas Salk wiped out polio with his vaccine, we would greatly expand the potential of all Americans to live long, healthy and productive lives — and save trillions of dollars doing it.

O’Connor, Prusiner, and Dychtwald offer science-based hope that a cure, or at least a significant improvement, is possible within a decade:

A breakthrough is possible by 2020, leading Alzheimer’s scientists agree, with a well-designed and adequately financed national strategic plan. Congress has before it legislation that would raise the annual federal investment in Alzheimer’s research to $2 billion, and require that the president designate an official whose sole job would be to develop and execute a strategy against Alzheimer’s. If lawmakers could pass this legislation in their coming lame-duck session, they would take a serious first step toward meeting the 2020 goal.

Yet unfortunately, if past is prologue, we can expect that the leadership of both parties will ignore O'Connor's argument, and Shriver's, because it doesn't jibe with their health-insurance-centric healthcare agenda. Indeed, the changes needed to make the quest for cures a viable proposition once again--concerning tort law, the FDA, and information sharing--are so enormous that both parties might conclude that it is easier to fight the same old fight about Obamacare. And it would be easier for the parties, indeed, if we simply refought the policy fight of the last two years over the the next two years--or 20 years.

But that fight, in and of itself, won’t do a thing to cure AD. And yet it’s a cure that the country needs and that the voters will reward.

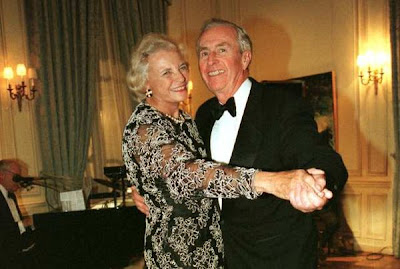

Pictured above: Sandra Day O'Connor and her late husband, John J. O'Connor, who died of AD in November 2009.

Is My Doctor Qualified?

2 days ago