“In a Land of the Aging, Children Counter Alzheimer's”--that’s the

headline, datelined Seongnam, South Korea, in The New York Times this morning. In that story, we see seeds of hope on Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)--not only for South Korea, but for the rest of the world. Indeed, here in the US, the challenge is to get our policymakers to consider lessons, and to seize opportunities, from overseas as part of our own medical--and fiscal--strategy.

Times Reporter Pam Belluck, alongside another Times reporter, Gina Kolata, has performed a great service,

opening our eyes to the worldwide dimensions of AD. In traveling around the world, covering what is, in fact, an international epidemic, she reminds Americans that we are not alone in this problem--and that we have many potential allies, if we can figure out how to ally with them.

In South Korea, a full nine percent of the population suffers from AD, compared to less than two percent of the population of the US. And because advanced cases of AD require round-the-clock care, the disease is horrendously expensive to treat. In the US, we already spend about $170 billion on AD, more than one percent of our GDP on AD; in South Korea, where the diseases is more than four times as prevalent, the burden is even greater. And of course, there’s the even greater financial cost of lost productivity--not only for the afflicted, but also among caregivers--as well as the enormous humanitarian toll.

For their part, the South Koreans are taking positive measures. According to the

Times, South Koreans freely describe their anti-AD effort as a “war.” And with a war comes society-wide mobilization. (Yes, as we know, the South Koreans are also, of necessity on a war footing against North Korea; the fact that South Korea is under so much pressure, from so many directions, is an argument for the full utilization of productive resources, including helping people stay productive for as long as possible, so that their skills and talents can be utilized for the defense of the nation, as well as for medical cures.)

Indeed, the South Koreans are taking positive measures against AD. They are organizing students to be part of caregiving, and consciousness-raising. Belluck describes some of the lessons being drilled into a young student:

“Dementia is very bad for you, so protect your brain,” he said, with exercise, “not drinking too much sugar,” and saying, “ ‘Daddy, don’t drink so much because it’s not good for dementia.’ ”

At a Dementia March outside the World Cup Soccer Stadium, children carried signs promoting Dr. Yang’s Mapo district center: “Make the Brain Smile!” and “How is Your Memory? Free diagnosis center in Mapo.”

One might say that such efforts, in and of themselves, have limited value. After all, right now AD is incurable; indeed, there is no real evidence that any sort of screening or palliative therapy does much good. Yet still, it’s important to start somewhere; building a consciousness about AD is a way of signaling to other aspects of society that AD is a problem, and that will hopefully trigger a problem-solving response. In the words of one anti-AD activist:

“I feel as if a tsunami’s coming,” said Lee Sung-hee, the South Korean Alzheimer’s Association president, who trains nursing home staff members, but also thousands who regularly interact with the elderly: bus drivers, tellers, hairstylists, postal workers. “Sometimes I think I want to run away,” she said. “But even the highest mountain, just worrying does not move anything, but if you choose one area and move stone by stone, you pave a way to move the whole mountain.”

So the South Koreans are mobilized and motivated. And given the miraculous rise of the South Korean economy--actually, nothing miraculous about it, South Korea has simply outworked and outproduced most other countries--we should allow for the possibility that South Korea, on its own, could generate a medical breakthrough on AD. And of course, were South Korea to accomplish such a breakthrough, the country would have developed yet another export industry, featuring a medical product that could be sold to the world.

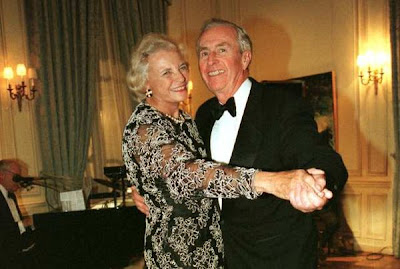

But of course, the South Koreans aren’t there yet, and maybe they will never reach that point--at least by themselves. Today, the greatest resources for treating and perhaps curing AD are in the US, although there’s shockingly little policy focus on developing a cure here--as Sandra Day O’Connor and two co-authors

recently pointed out, we spend 350 times more on AD treatment than we do on an AD cure. That’s about as penny-wise and dollar-foolish as we can get. And in addition, hurdles of regulation and litigation are seemingly designed to block progress: the crucial progress of “translation”--that is, turning a bright idea into an effective drug.

George Vradenburg, co-founder of

US Against Alzheimer’s, suggests that one way to accelerate progress against AD is to build a “network of excellence” around the world, in which different research nodes--institutes, cities, even entire countries--could contribute to developing the knowledge base needed for a cure, as opposed to mere care. Such a network is in keeping with the spirit of the Internet, and that’s not surprising, since Vradenburg was one of the visionaries behind the meteoric growth of AOL back in the 90s. But of course, as Vradenburg is fully aware, the development of such a network would require a significant rethinking of laws and regulations concerning not only liability, but also privacy and intellectual property. Indeed, since the creation of such an anti-AD network would be so complicated, genuine leadership--public, private, civic--would be required to fully mobilize available resources. So no, there’s no guarantee that such new networking can, in fact, be realized.

But one guarantee we can make is that progress against AD would accelerate if we could develop a robust AD information network, because as Bob Metcalfe was the first to articulate, the processing power of a network is the square of the number of participants in the network.

And an even firmer--and grimmer--guarantee we can make is that AD costs will be ruinous if present trends continue. Not just in the US, not just South Korea, but around the world.

Meanwhile, back in the US, we can note that three recent deficit reports--one from a presidential commission, co-chaired by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, another from the Bipartisan Policy Center, led by Alice Rivlin and Pete Domenici, and a third report, from Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL), have all weighed in with ideas for dealing with future deficits--each venturing different ratios of spending cuts and tax adjustments and/or increases. What’s remarkable, though, is that none of these deficit groups, however well-meaning, seem to have thought in international terms about how to solve problems. For all the talk about “globalization” these past few decades, our policy process seems strangely parochial.

What would have happened if the deficiteers here in the US had communicated with the South Koreans about a pooling strategy for AD research? And with the Japanese? And with Germany, China, and all the other rich countries that confront rapidly rising AD? What sort of answers would have emerged from such networked thinking? Answers including, perhaps, prospects for a cure, or even a significant easing of AD onset? Or other ideas? For example, the Japanese are making a huge investment in robots, many of them designed for geriatric care. The world outside of Japan might not be ready for “geri-bots,” but maybe we will be ready in another decade?

Indeed, what’s so striking about the deficit debate here in the US is how limited it has been, in its intellectual scope.

And so we come to a paradox: We need to think ahead, and think freely, even as we keep our perspective about what, precisely, can be known. Throughout history--it has been virtually impossible to see, with any degree of accuracy, what the world will be like 50 years ahead. So all straight-line projections are bound to be wrong. That was the fate, for example, of Thomas Malthus, who predicted that England would run out of food in the 19th century, or Paul Ehrlich, who predicted worldwide starvation in the late 20th century. Of course, it’s not just population projections that are proven wrong. In 1865 the eminent economist William Stanley Jevons predicted that England would run out of coal in the 20th century and so argued for cutbacks in his own time. While Jevons was right about the limitations of English coal reserves, he missed the impact of petroleum, which had in fact, been discovered seven years earlier. Similarly, those today who hypothesize about “peak oil” have similarly missed not only the ever-greater discoveries of coal and oil, but also the emergence of vast new natural gas resources.

Returning to health, we can recall a US government estimate from 1950, projecting national expenditures for polio by the year 2000 at $100 billion. Adjusted for inflation that $100 billion would be about $1 trillion today. Such an expenditure would have been a huge burden on the government and on the economy, but of course, it didn’t happen--because we developed the vaccine for polio back in 1955.

The point here is not to make fun of earnest efforts at forecasting the future--although we might note that many forecasts are not earnest, but rather part of a different political and intellectual agenda. Instead, the point is argue for a bit of humility, and, at the same time, to argue that in technology issues, the optimists are usually right, at least in an overall sense. If we allow scientific inquiry its free rein, we will more often than not be pleasantly surprised by what we come up with.

And so the deficit groups of 2010, as they sought to save us from fiscal wreck in 2030 or 2050 and beyond, would have better served the rest of us if they had factored in the best guesses of scientists and medical researchers. Answers from experts would have been all over the spectrum, of course, but it might have been possible to tease out solutions for not only cutting costs, but also for improving personal health and economic productivity.

In fact, it would have been useful to include other forward-thinkers as well. Not because, as we have seen, all forecasts are correct--just the opposite, in fact--but because forecasters and trendspotters can at least point us in the right direction. And the right direction is technological improvements and productivity growth, which are inevitably coupled with per-unit cost reductions.

Moreover, this forward-looking consultation process could have been international. We could have reached out to the South Koreans, and to the Japanese, and others, and said, “How are we going to pool our resources so that we can solve the AD problem?”

Yet instead, the deficit commissions chose to see everything in purely parochial US terms. And yet absent the transformative potential of technology, the ideas that two of the three commissions--Bowles-Simpson and Bipartisan Policy Center--had for cutting spending, such as imposing the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) on Medicare doctors--will never happen, or at least not in any time frame that the deficiteers envision. The SGR is always pushed back by Congress, because Congress is receptive to the popular demand that seniors should get the best possible medical care, from the widest possible selection of doctors.

An article in today’s

Washington Post this morning provides an example of the hard pushback to come; the doctors will almost certainly beat back the SGR, now, and for years to come.

As for the Schakowsky report, calls for big tax increases are similarly unpopular, and thus improbable.

So we get back to an oft-made point: If a big chunk of our population ages and sickens with AD, it will be expensive, no matter what the financing or rationing scheme. The better answer is to cure the disease. Such a cure might be a long time coming, but the spinoffs along the way will be valuable, and the goal itself will be even more valuable.